Aligning everyone’s understanding of “what is acceptable” and “what is not acceptable” into a quality standard is very important. And it is not easy.

Different customers have different tolerances for the same type of defect on the exact same product. For example, some may accept a small dent, while others won’t.

The most common elements of a quality standard are as follows.

Product specifications

What should the materials be? What should the dimensions be, with what tolerances? How should function testing be carried out, and what is the expected result?

This is the master document that includes your requirements and quantifies them as much as possible. Show photos of what you want, and of what you don’t want (if you have any such example at hand).

If you prepare specifications, the manufacturer should base their checklist on your document. If you don’t, they should still have a checklist in hand, but don’t expect their checklist to be very detailed.

Packing specifications

This is the same idea. Packing specs are often included in the product specs, but we mention it here because many inexperienced buyers forget to specify what packaging & export packing they want in their quality standard.

This is important not only to protect the product and its unit packaging, but also to comply with the specific requirements of the distribution channel.

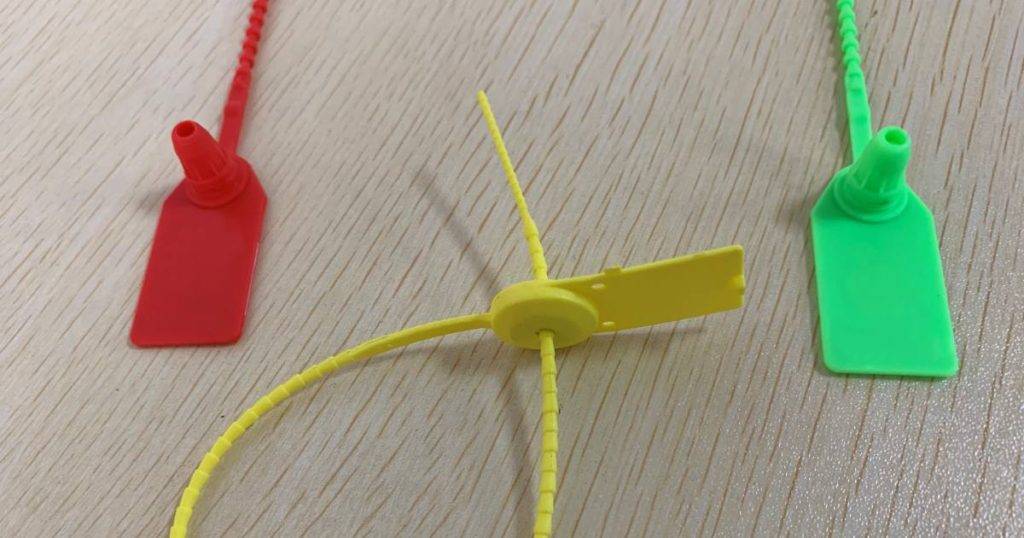

An approved sample (in each color)

Not everything can be described with words and photos. It is customary for the buyer to approve a final sample, and to send one back to the manufacturer with proper identification.

Many companies use seals that make sense for their products. A yellow seal can be used for this “golden sample”.

Now, what if there is no time to make a perfect prototype, and the customer insists to move immediately to the next phase (for example, making the tooling)? The customer should try hard to give a very detailed account of what he likes, doesn’t like, and is afraid might appear in the next round (on the pre-production samples).

By the way, once samples are made with the proper tooling and with mass-produced components, some details of the products may necessarily be different. For example, a molded plastic product always has an injection gate which, even though it can be trimmed, might have a small visual effect. If you can’t tolerate that uncertainty, make sure to communicate this with the manufacturer in order to collect more information and make an informed decision… before the investment in the tooling is decided.

Limits of the “one approved sample” approach

Let’s say you have one approved sample. It will be useful to compare with mass production. However, there is always some variation, and you should be ready to accept a certain amount of variation. The difficulty lies in setting rules that enable objective judgement.

If you are planning to make a product in high quantity, spending time at this stage is very important, since any quality issue might be very costly.

Defective samples

When the components are made, some defective parts will be generated. When the product is assembled, same thing. Keeping these examples is very educational. Take photos of them to alert the production and quality staff about potential issues they should have an eye out for.

Even better, collect a number of defective samples and place them on shelves at the factory. It is a great tool for training operators and inspectors.

Boundary/limit samples

Let’s say you want the plastic to be a certain grade of blue. You indicate a Pantone code in your specification sheet. You approve a golden sample that is just the right blue. However, the plastic part supplier can’t promise they will get that exact same shade of blue just right.

The solution? At the same time as they make shots for the approved sample, have them make a few samples a bit lighter, and a few others a bit darker. Use these boundary or limit samples to approve the boundaries of your acceptance criteria.

This is not only useful for colors. For example, blemishes on a plated metal surface will be much more visible in certain colors, and boundary samples (with very small, small, and medium blemishes) will allow you to indicate what you can and cannot accept.

Further reading: Read more about golden samples and limit samples.

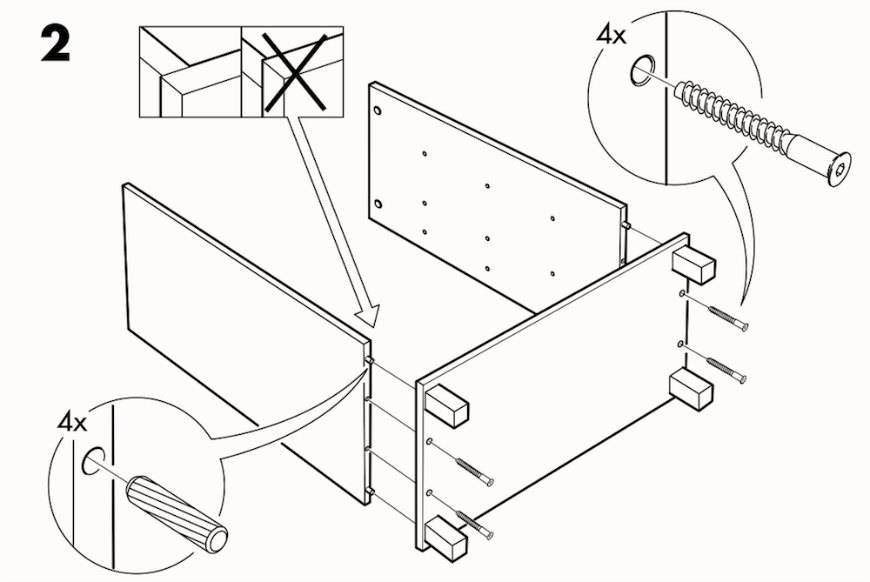

And if you have also designed the process… assembly instructions!

Some buyers have already done some process engineering work and know exactly how the product should be assembled. This has to be communicated to the manufacturer.

A well-known best practice is to cut it into discrete operations and to use drawings (or photos with arrows, dashed lines, etc. added) to convey the idea for each operation. Here is an example from Ikea:

Someone who can’t read your language will be able to understand how to do this. It can then be re-used in any country.

Who should be given this information?

The customer and the supplier (typically the manufacturer that does the assembly and might do some fabrication) need a copy of each element of the quality standard, obviously.

Component suppliers also need to receive very clear instructions on what they are expected to do. They should be given clear specifications and samples, in addition to drawings.

And, finally, if you engage someone to do inspections on product quality, that person also needs to have all that information.

*****

Have you devised a quality standard of your own yet? What challenges did you find in the process? Let us know in the comments.

Unsure where to get started? Contact us and we can discuss your manufacturing project and see how and where we can assist you with getting your products from design, to mass production, to shipped out to you.

Want even more information on this topic? You may also find this blog post from QualityInspection.org interesting: 4 Proven Ways To Enforce A Quality Standard In China