The more novel and the more complex a product design is, the higher the risks of running into technical issues.

In fact, a complex new product is almost guaranteed to come with all sorts of challenges and problems. And that’s even more true if there is no attempt at forecasting and addressing those challenges and problems preventively… with tools such as the Design FMEA and the FTA.

What is an FMEA?

FMEA stands for Failure Modes & Effects Analysis. It is basically a risk analysis. ‘Failure modes’ are the issues you foresee as somewhat likely to appear.

It is a very structured approach. It breaks down risk into 3 components:

- The severity of the impact (on the customer, on the organization…)

- The likelihood that the event actually happens

- The controls currently in place to address that risk (ideally, those controls lead to systematic early detection & reaction)

Each failure mode is scored on each of these 3 components. Those scores are them multiplied, and the composite score (“RPN”) allows engineers and managers to prioritize those risks.

And finally, it prompts the question of “what should we do about this”. It becomes an action plan!

What about a Design FMEA?

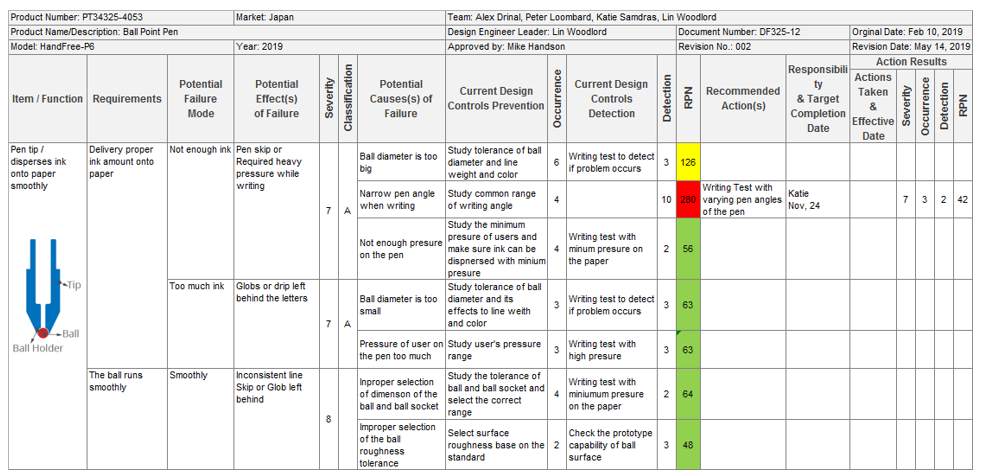

A design FMEA is a risk analysis conducted at the product design phase. Here is a good example about a ball point pen.

Design FMEA example source.

It is a bottom-up approach. Starting from each part and/or each functionality, an engineer wonders what can go wrong. Based on that list, and based on the risk prioritization mechanism inherent in this template, he works on an action plan to reduce the highest risks.

You can learn more about how to successfully implement a dFMEA here: dFMEA: 8 Secrets for a Successful Implementation

A nice complement to the DFMEA: the Fault Tree Analysis (FTA)

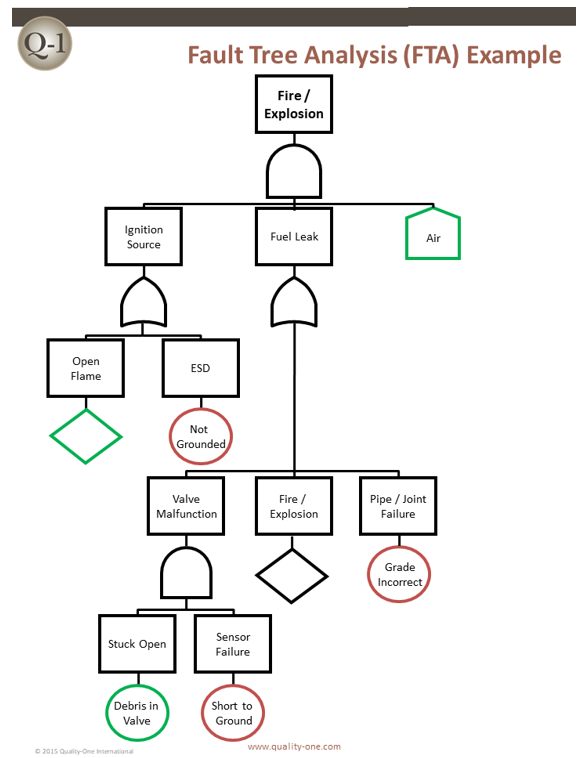

In addition to the FMEA’s bottom-up approach, a top-down approach can also yield interesting insights. Enter the FTA — Fault Tree Analysis.

It does not follow a highly structured template. Here is one example:

Here is the FTA image Source.

It starts from the issues typically feared (e.g. a plane engine stops working, a traffic light gets stuck on green…) and it explores “what would have to happen, to make this possible?”.

Once the potential causes (shown in a circle, in the graph above), probabilities can be estimated and action plans can be drawn up.

What information is needed before starting a DFMEA or a FTA?

Obviously, the engineers running those analyses need to know the list of parts and features of the product. They also need to know the expected conditions and manner of use, what the project managers and the users would consider as very serious failures, and so on.

The more information is available, the better. It provides good guidance.

Why is it better to do risk analyses early in the design & develop phases?

Studies have shown that catching an issue at the initial design stage (rather than on a prototype) is 10 times cheaper (in time and money). And, similarly, when issues are fixed at the prototyping stage rather than in production, the cost ratio is again 1 to 10 times.

A design with fewer failure modes will lead to:

- Easier production (which usually translated into better quality, lower costs, and less delays)

- More robust design, less likely to fail in the users’ hands

Who typically does a DFMEA?

The R&D team generally leads this exercise, but it should be done together with representatives of the quality, purchasing, and production groups (and others if possible). It is a must to bring different perspectives to the table!

How to confirm if some of the risks highlighted are real?

In some cases, engineers have no idea if a failure mode is likely to come up. That’s why they often do ‘proof of concept’ prototypes and test them. Later in the development process, prototypes may be tested to failure, and again pre-production samples may go through the same treatment.

Do all risks need to be addressed?

The FMEA analysis will tend to point attention to the highest risks. If there are 100 potential failure modes, it generally makes little sense to try and mitigate all of them.

Also, in some cases, you may not be able to prevent an issue from happening. Can you, instead, add controls so that it is detected before the product is shipped out? Or, in the worst case, can the product alert users before they are at risk (think of the alert lights on a car’s dashboard)?

You may also like…

- How To Qualify Component Suppliers At The Design & Prototyping Stage

- NPI Process #1. Why A Pilot Run On A New Product, Before Mass Production, Is Very Helpful

Get involved!

Do you have any questions about this topic or experiences to share? Maybe you need help with your product development? Please leave us a comment or hit the button to contact us:

About Renaud Anjoran

Renaud is a recognised expert in quality, reliability, and supply chain issues and is Agilian's Executive VP. He has decades of experience in electronics, textiles, plastic injection, die casting, eyewear, furniture, oil & gas, and paint. He is also an ASQ-Certified ‘Quality Engineer’, ‘Reliability Engineer’, and ‘Quality Manager’, and a certified ISO 9001, 13485, and 14001 Lead Auditor.