![What Can Entrepreneurs Learn From Dyson [Case Study]](https://www.agiliantech.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/What-Can-Entrepreneurs-Learn-From-Dyson-Case-Study.jpeg)

The autobiography of Sir James Dyson, British inventor of the wildly successful Dyson vacuum cleaner: Invention: A Life on their website is a fascinating look into his life, designs, methodology, and products.

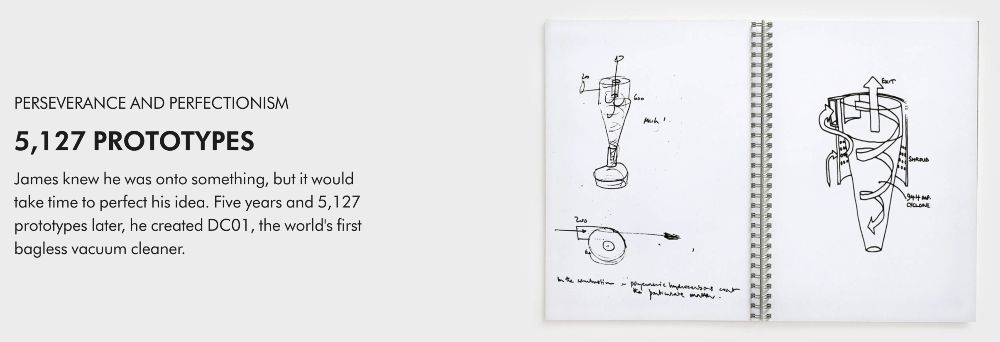

People have heard about the 5,000+ prototypes he worked on before making a vacuum cleaner based on cyclone technology that could work well, but they usually don’t know the full story…

The background

- He had previous business experience as the GM of a successful boat company and as the inventor-founder of a not-so-successful wheel barrel company, the ‘ballbarrow.’

The barrow’s unconventional design is obvious and the ‘ball’ has been an enduring feature of Dyson’s designs:

(Image credit: Top 10 machines developed by Dyson, Telegraph.co.uk) - The experts in the cyclone technology all agreed on the fact that it was impossible to use this technology for particles of dust under 20 microns, while Dyson wanted it to work for particles as small as 3 microns.

- There were several mathematical formulas to represent how that technology worked, and all agreed on the fact that Dyson’s goal was impossible.

- The big competitors such as Hoover and Electrolux might already have considered that possibility, but they didn’t launch anything. And they had a good reason for it — they were making good money from the sale of consumables (the bags that have to be replaced as soon as they are a bit full and make suction difficult).

- Dyson set out to prove the experts wrong by performing empirical tests. And something clear comes out of his autobiography: the one trait he certainly doesn’t lack is persistence:

(Image credit: James Dyson Foundation website) - The 5,000+ prototypes over 5 years were only ‘proof of concept’ prototypes to confirm that the core technology could work on the general application of vacuum cleaners, and it took more iterations to make the whole product what it was in its first commercial version. There were a few iterations under different brands in the early days, but the first commercially successful Dyson-branded bagless vacuum was the DC01 from 1993:

(Image credit: vacuumland.org)

Getting the company off the ground

- He developed a superior product, with a different business model (not relying on recurring sales of bags), and that made his entry into mainstream retail chains more difficult. It was a new concept that salespeople had to explain to customers.

- He fell deeply into debt to finance it. He took a great personal risk for years. If investment in promising tech companies were as widely available as it is now, I guess he would have seriously contemplated that source of funding.

- He had a very hard time finding licensees (harder than finding customers), and he was even sued by a licensee who later copied his design and had to be sued in the USA. In the end, he had to admit that nearly all his licensing agreements had failed, which prompted him to start manufacturing in the UK.

- He lamented the difficulty and expense of getting patents respected. The patent system is quite imperfect and inventors can’t just count on it.

Difficulties with manufacturing

- They started manufacturing in the UK but faced tremendous difficulties with their local suppliers there. For example, an American-owned plastic manufacturer in the UK doubled pricing suddenly, and Dyson needed a court order to pull the molds from their facility.

- Once sales rose, they couldn’t get a permit to enlarge their existing manufacturing facility. And, after some time, they only had one supplier left in the UK, and that supplier was reluctant to increase their capacity beyond a certain level.

- At one point, since most of the plastic and electronic part suppliers were in Asia, it made more sense to move assembly there (to Malaysia, specifically). They were not chasing cheap labor (or they’d have picked China or Vietnam), and it made much more sense from a supply chain point of view.

Some good practices that make sense for them

- They work with contract manufacturers for most of their assembly work, rather than doing all the production in house, which would be very hard with a 25% yearly growth. They only want to manufacture the components/subassemblies that embed their core technologies by themselves.

- Those contract manufacturers are not necessarily already experts in making vacuum cleaners, hair driers, etc., but the Dyson engineers can teach them how to do it well.

- They chose Singapore for some of their advanced manufacturing, some of their R&D, and finally for their global headquarters, too. Developing innovative products and making them at high quality is much easier if the components are made close to assembly, and if R&D centers are close by, too. Not to mention, Asia is their fastest-growing market. Here’s their new global HQ building, the St. James 1920s power station in Singapore:

(Image credit: © Wikimedia Commons User:Sengkang / CC-BY-SA-3.0) - They take product reliability very seriously – for example, they set up a “torture course” for prototypes – it helped them make products that use as little material as possible while still being reliable enough to fulfil customer needs. New Dyson vacuum cleaners also come with a 5-year warranty (in the UK at least), longer than many of their competitors’ warranties.

- They see themselves as a tech company. They employ thousands of engineers. They keep deepening their expertise in their core technologies and they keep looking for new applications that will answer customer needs.

- When they launched a new type of hair drier, they certainly went at it in a structured manner, but they didn’t try to avoid technical challenges. It took them 4 years, 55 million GBP, 103 engineers, and 600 prototypes. The end result is the ‘Supersonic’ hairdryer:

(Image credit: Stuff.tv)

Your thoughts..?

It’s an easy-to-read autobiography, so grab it if you have an interest in these topics!

Does the way Dyson has gone about designing and developing his products and building a disruptive and very successful business resonate with you? Let me know your thoughts by commenting, please.

P.S. you might like this video…

James Dyson explains their approach to engineering in this video:

P.P.S.

As you’ll learn, Dyson takes IP protection very seriously and has embarked on numerous high-profile legal cases in order to safeguard their product IP. Taking steps to protect your IP is really important for any entrepreneur with a dream to bring their innovative new product, like Dyson’s bagless cyclonic vacuum cleaner, to market.

To help you do this safely, I’ve written a guide to IP protection when developing a new product to be manufactured in China. It’s FREE and you can read it on Sofeast.com now:

![Sofeast IP Protection in China when Developing Your New Product [Importer's Guide] Sofeast IP Protection in China when Developing Your New Product [Importer's Guide]](https://www.agiliantech.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/IP-Protection-in-China-when-Developing-Your-New-Product-Importers-Guide-300x169.jpeg)