When introducing a new product, Chinese suppliers often hasten their customers into mass production. While getting the product into production quickly may at first sound attractive, this rush, primarily driven by the suppliers’ financial interests, can overlook essential steps in the NPI (New Product Introduction) process. Instead of jumping straight from prototype to mass production, which is risky, bridge production offers a valuable alternative.

This article explores the advantages of bridge production, the trade-offs involved, and how this approach can help deliver products to early customers more efficiently.

Why the rush to get your new product into production?

When developing a new product, most Chinese suppliers push their customers to go into mass production as fast as possible. And, even before the end of product development, they often push their customers to send money to make tooling (typically for custom-designed plastic parts).

All of this is in the supplier’s interest since they only make money once production is underway. Unfortunately, it is not in your best interest for several reasons.

First, as we explained before, certain steps of the NPI process should not be skipped. That’s a general truth for nearly all electrical, electronic, and/or mechanical products.

Second, the direct path “from prototype to mass production” is not always the best. In particular, we noticed a lot of companies have already committed to delivering some products to early backers or early customers, and they feel a strong sense of urgency.

Is there an alternative to go into mass production in order to deliver to customers?

In general, new product launches assume that the product will get industrialized (i.e. the manufacturing & testing processes are designed, developed, and validated) and good units will be shipped to customers.

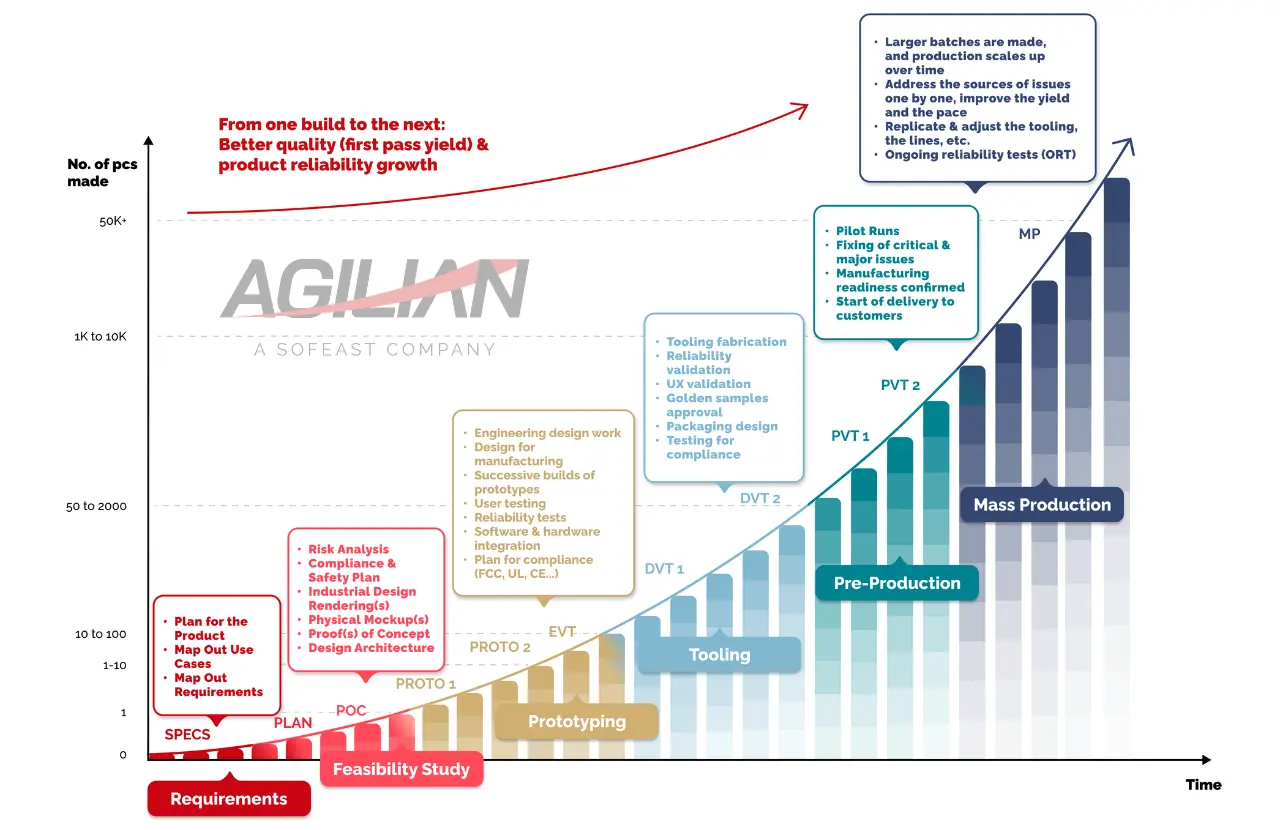

You can see the NPI process we follow and its phases here:

Under that logic, all the tooling (if any) is fabricated, and all the parts are made with production-intent processes before even small pilot runs of 50 or 100 pieces take place. And that takes time (often 6+ weeks).

Bridge production

The good news is, there is an alternative, and it’s called a bridge production run.

Sometimes a startup needs a bridge financing round between, say, the A round and the B round. The CEO has to convince venture capitalists to provide more funds, usually at an inferior valuation, but in those cases, the lower valuation is acceptable to the founders because it allows them to hit higher-level business objectives.

The same logic applies here. Bridge production is a less-than-ideal but acceptable fix to an urgent need.

How early is early?

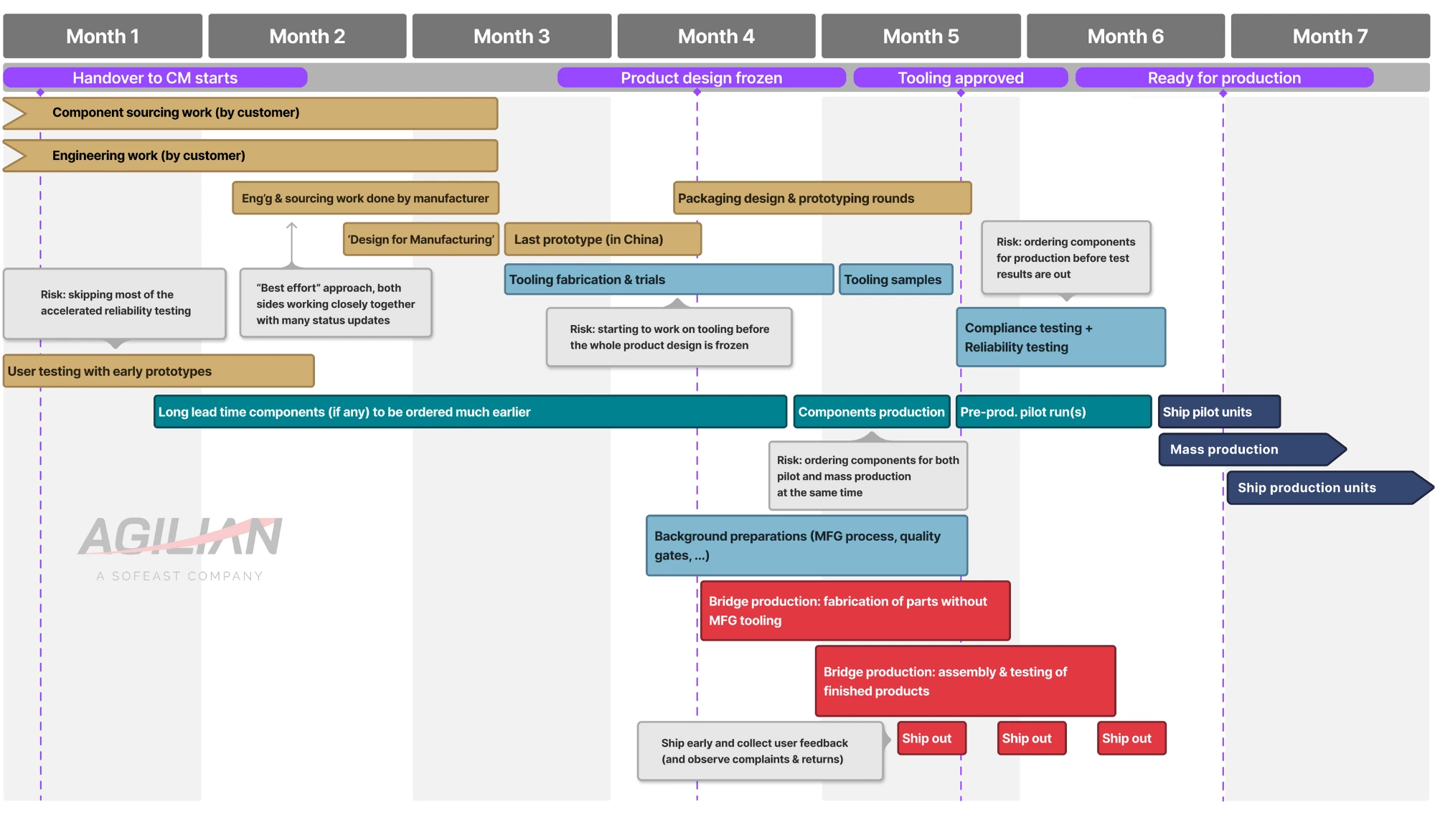

You can see when bridge production would take place during a new product launch period here (it’s the red parts of the chart):

It typically starts after the product design is frozen, but before the final production tooling has been approved, and bridges the gap between tooling being made and production starting. A few short bursts of products are delivered which can help get user feedback and performance results from the field before large quantities are produced.

What trade-offs can be made?

There is an urgent need to deliver some sufficiently functional and sufficiently aesthetically pleasing products to certain customers. It is often in the hundreds or the thousands of pieces, and seldom in larger quantities.

These products do not necessarily need to be identical to the products that would be mass-produced later. Actually, they can’t. Production tooling is not ready, some of the software features may yet to be developed, and the testing stations may not work yet.

So, these early products might come with one or two fewer functions.

They might be more brittle than mass-produced products because of 3D printing.

They may not even need to be fully in compliance with applicable regulations, exploiting the tolerance of certain agencies (e.g. FCC) for the initial small production runs.

A visual imperfection may be acceptable.

And so on.

But they need to make these early customers happy. Or “happy enough”.

How is bridge production done?

As I wrote above, the two main differences with typical mass production are:

- The product development may not be fully completed, so it is a “version 0.9 while waiting for version 1.0” in a way, and/or

- Different manufacturing processes are used to make the custom-designed parts.

Let’s look at the second point – different processes.

Many plastic or metal parts can be 3D printed or machined out of a block of material. Sometimes, if a part can be de-molded easily, vacuum casting makes sense, too.

Some companies have been working on ways to bridge the gap, if I may say, between prototyping and mass production processes. 3D printed injection tooling is possible, and one set of tooling can often be used to make ten, twenty, and sometimes even more pieces. This process can gradually be improved by adding metal inserts, making a part of the tooling in metal, and so on, without having to wait for the full mold to be cut from steel or aluminum.

Are products made in a bridge production run sold at a premium?

That’s very variable. It really depends on the project.

Often, they are actually sold at a discount. Think of the first backers of a Kickstarter campaign – they usually pay a lower price.

However, we have seen companies that use prototyping methods to start selling products, and they could actually finance the rest of their development efforts that way. Things often took longer, but the product was ultimately solid, as it incorporated a lot of users’ feedback.

In any case, the unit cost of a bridge run is often higher than in mass production, but that’s not a universal law. A “version 0.9” product with a few 3D printed parts and no tooling to amortize on the unit cost might be cheaper than mass-production units.

Remember, in most cases making a little detour on a “bridge” makes sense when there is a strong urge to deliver hundreds or thousands of pieces quickly to some early customers. Making a nice margin is usually not an objective.

Why is it so important to deliver some products earlier to a select group of customers?

Typically, if you have raised money, have promised some large partners or retailers that production would be available soon, and if product development took longer than planned (what a surprise!), you are under intense pressure. You don’t want them to lose patience and write you off.

It’s the same story if you did a crowdfunding campaign and some of the backers complain in a very loud manner. It’s like a baby crying for a toy… You want to get something into their hands, now.

Does it help improve the product?

Yes, and that’s a major benefit of delivering devices several months before high-quantity production starts.

Despite a lot of reliability testing, there is always a risk of shipping products and getting a high rate of return. Maybe the assumptions of what type of users would buy the product were somewhat wrong (for consumer goods). Perhaps the product is not used in the expected conditions. Maybe a big B2B customer did not fully disclose the stresses imposed on the product for fear of a much higher price (!).

So, in a way, shipping more than 50 products to target users is a form of reliability validation. If the type and proportion of complaints & returns is alarming, a design adjustment may be needed.

In addition, if you pick some “Innovators” or “early adopters”, as Geoffrey Moore called certain customers, some may provide good insights and suggestions that you can act upon.

Any other reason to do a bridge production run and deliver products early?

There are many ways to pre-sell your product, especially if you sell your product B2B:

- You may need to work with industrial or utility customers that need a few units for a pilot

- You may go to trade shows in a particular industry.

- You may approach companies directly.

In any case, it’s the same idea. You pre-sell your product. You deliver some products earlier. You keep those customers interested, you earn trust, and you make progress in your sales process with them. And you capture customer feedback, ideally when you still have time to tweak the ‘version 1.0’ product design.

Finally, it’s a tool for you to test the market. Some companies do a Kickstarter campaign and are unsure which color/s their customers will prefer. They don’t trust pre-campaign surveys on that topic. There is a solution:

- Offer your product in four different colors

- Let your backers vote with their money

- One or two colors may be above the MOQ and can be made with mass-production intent processes

- The other colors have to be made with prototyping methods, for example, the parts may come out in the exact color you want from the 3D printers, or they might have to be painted anyway

Is there a limit to the quantity of bridge manufacturing products?

In theory, no. Let’s say you need to be aware of the limitations of the prototyping technology you will use.

If you need 2,000 hours of SLA 3D printing, all compressed into 3 weeks, that can be purchased relatively easily from one of the large 3D printing factories (and they might subcontract a part of the job to a few other factories, but it is feasible).

On the other hand, 10 years ago, some smart people tried to 3D print laptops for mass production. They quickly pivoted. 3D printing was nowhere near fast enough.

And what large companies can do, you may not be able to do. You probably can’t buy thousands of CNC machines to machine your laptop enclosure the way Apple did.